Kvasir Symbol Database

Water, water body, & ship

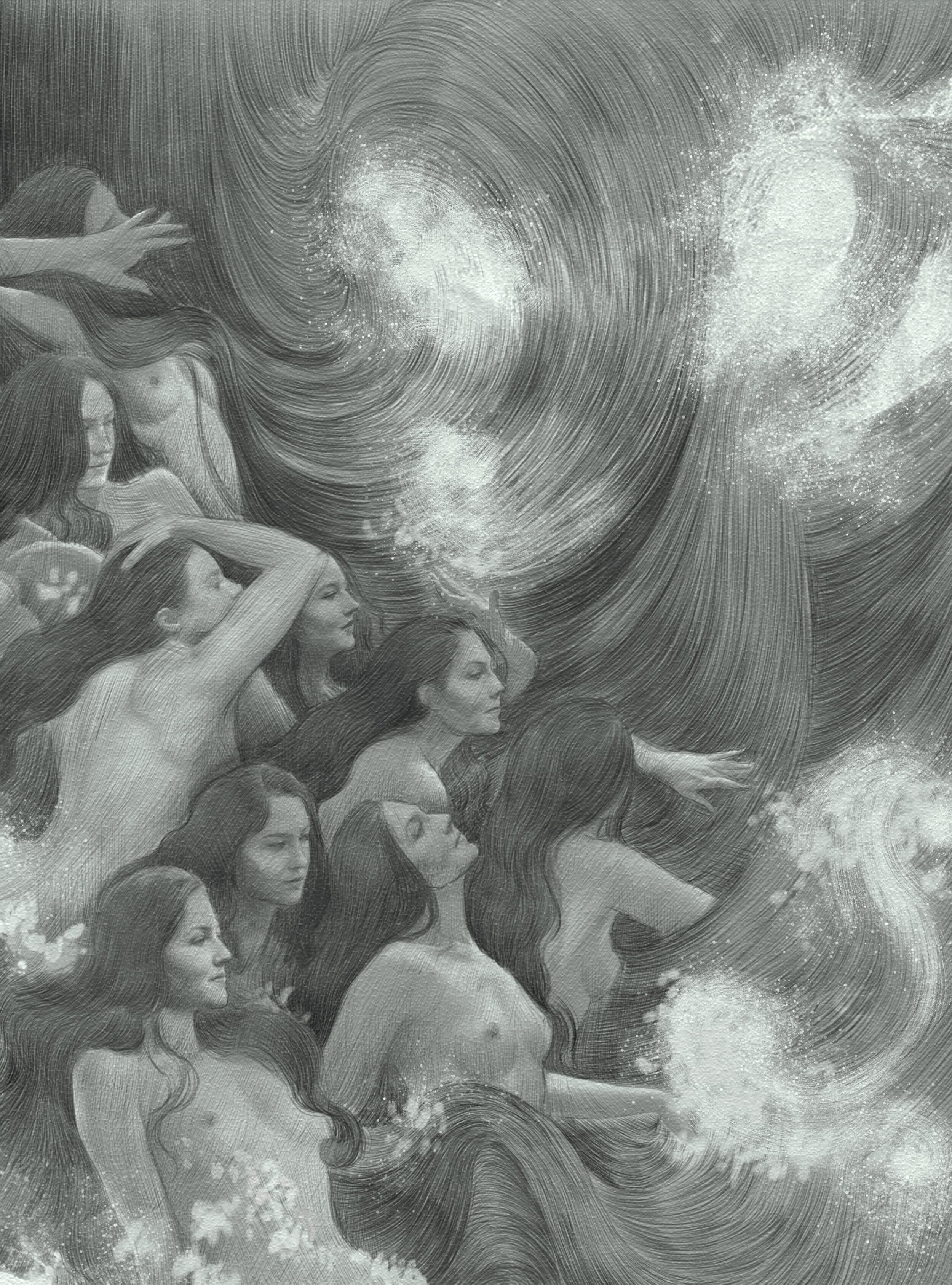

Image I: The Nine Daughters of Rán and Ægir, the personified waves. Rim Baudey for Mimisbrunnr.info, 2020

Entry by Joseph S. Hopkins with art by Rim Baudey for Mimisbrunnr.info, February 2021

Updated March 2025.

Quick reference:

Hopkins, Joseph S. 2020. “Water, water body, & ship”. Mimisbrunnr.info. URL: https://www.mimisbrunnr.info/ksd-water

Description & dating

Water is a chemical substance necessary for all life on Earth. It covers much of the planet (primarily in liquid form) and is the central component of the planet’s hydrosphere.

Water is a necessary part of everyday life, and it therefore has played a central role in the life of every human being throughout the entire history of humanity. Humans must consume clean water on a regular basis and so must therefore always live within range of ready access to water. As with any other animal, all decisions and actions in a human’s life rotate in some way or another around access to potable water.

Sources

As one would expect from something so fundamental to human life, water is an extremely common topic in folklore. Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature alone lists thousands of water-associated motifs (for example, compare Thompson 1955: 849-853, and the numerous other entries associated with water, such as mermaid, washing, and so forth). Clearly, this entry would need to be truly immense to cover every facet of the topic in the ancient Germanic record. Therefore, we can only touch upon a handful of topics here.

Important to address here, too, is the dependence upon North Germanic sources for many of these topics. Of course, bordering the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean, much of Scandinavia is well known for its long coastlines, islands, and open seas. However, this is not the case among the non-coastal ancient Germanic peoples on the continent, where one might easily live a life without ever seeing a sea, ocean, or comparable body of salt water. Keeping in mind the diversity of biota and geology that the ancient Germanic peoples encountered makes for important perspective when discussing the Proto-Germanic period and beyond, particularly among continental Germanic groups.

Finally, before beginning this discussion, a topic common in scholarship in this area will surface here and there: The concept of animism. As with any similar concepts, definition can be slippery, but for the purpose of this entry we’ll be using a definition of the term from the Oxford English Dictionary:

Animism, n. 2. “The attribution of life and personality (and sometimes a soul) to inanimate objects and natural phenomena.” (OED 2020)

Any time we discuss objects we today consider to be ‘inanimate’ (such as a stone, tree, or water body) in an ‘animate’ matter, we are working to some extent or another within this definition. However, this definition is also quite restrictive, as British scholar Graham Harvey notes in the introduction of the second edition (and in fact first edition also) of his Animism: Respecting the Living World (2017: xiii):

Animists are people who recognise that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship to others.

(Readers can view a 2019 lecture from Harvey for the Harvard Divinity School titled "We Have Always Been Animists" here.). Animism may occur in a variety of ways, including by way of personification and, as Harvey and scholars such as Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen (2020) point out, animism can be expressed in complex and intricate manners.

Water bodies: Living water & the watersheds of the mythical landscape

The most transparent example of personified water bodies in the ancient Germanic corpus is a particular family of entities, the result of the union of Rán and Ægir. In the Old Norse sources in which this couple are referenced, these two entities are repeatedly indicated to be straightforward personifications of the sea. Consider the example of Sonatorrek, traditionally attributed to 10th century Icelandic skald Egill Skallagrímsson. In this composition, the skald—a variety of poet—expresses his grief at the loss of his son, who died during a storm at sea. Egill repeatedly refers to the sea (in this case what we today call the Atlantic Ocean) as a fully personified couple, Ægir and Rán. These entities are referenced throughout Old Norse texts and are a component of what we today call Norse mythology, a body of narratives and references featuring North Germanic deities and deity-like entities. In these texts, Rán is described as an ásynja, a goddess (Skáldskaparmál; Faulkes 1998: 157), and Ægir is listed as a jǫtunn, one of those aforementioned deity-like entities (in the eddic poem Hymiskviða; cf. Neckel & Kuhn 1983: 88: jǫtunn and bergbúi, and Skáldskaparmál, Faulkes 1998: 111).

We are told in both the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda that together this couple produced Nine Daughters. Now, as discussed in Kvasir Symbol Database’s entry on numbers, nine and other multiples of three are supremely important throughout the ancient Germanic corpus, and so the number of the daughters here is no surprise. Yet as you’d expect from the union of two personifications of the sea, these are not just any daughters: These nine are in fact the personified waves (as explicitly stated in Helgakviða Hundingsbana I and a few times in Skáldskaparmál), and as anyone who lives by the sea knows, waves can be placid and gentle, beautiful and nurturing, or unforgiving and lethal, awe-inspiring in their potential for annihilation. One of their father’s names is Hlér, which, like Ægir, means ‘sea’ (while their mother’s name, Rán, means ‘thief, taker; she who takes’, an appropriate name for the rising tide, a grasping current, or even clawing waves).

It is by way of the name Hlér that Ægir is associated with an island off the northeast Jutlandic coast, nearly in the center of the Kattegat, a high-traffic section of the Baltic Sea. The island’s modern Danish name, Læsø, derives from the island’s Old Norse name Hlésey, a compound meaning ‘Hlér’s island’. It would seem the island had a particular association with these wave daughters as well: In the eddic poem Hárbarðsljóð, the god Thor recounts that when he visited this island, he was met with ferocious women who hammered his boat with a club:

‘Berserk women I battled in Hlésey;

they’d done the worst things, betrayed the whole people.

…

Wolves they were, scarcely women,

they rattled my ship which I’d beached on trestles,

they threatened me with an iron club and chased Þjálfi.

(Carolyne Larrington translation (2014: 71) modified by Hopkins, 2020.)

These ‘hardly women’ who ‘rattled Thor’s ship’ appear to be surging waves personified, none other than the Nine Daughters of Rán and Ægir, figuratively recounted as ‘berserkers’ angrily fending off Thor and his servant, Þjálfi—the angry waves who dare to club the mighty hammer-wielding god. The employment of the same motif occurs in Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, in which the poet author(s) refer to brutal waves pouring over a viking army at sea as the ‘daughters of Ægir’ and the sea is referred to as the ‘hand of Rán’ (cf. Neckel & Kuhn 1983: 134).

This is not the only time Thor is described as experiencing curious difficulties with bodies of water. Hárbarðsljóð is itself focused on the back-and-forth insults (the ritual custom of flyting) between Thor and another god, Odin, who is disguised as a ferryman. Odin can cross the water, but Thor cannot, and for this Odin needles the popular god. Indeed, Thor intrigues when considered through the lens of water. Etymologically, Thor is the personified thunder (Proto-Germanic *Þunraz literally ‘thunder’ and not, revealingly, the ‘thunderer’; cf. Orel 2003: 429), and so Thor is naturally associated with storms and rainfall. His wife, the goddess Sif, is repeatedly described by way of her long golden hair (the only such description of a Germanic goddess known to us) and her name occurs as a heiti for ‘earth, soil’ in Skáldskaparmál. This has led to many scholars over the years interpreting her representing the soil, the thirsty grain field to Thor’s thunder storm. The image of the powerful, personified storm over the rich earth from which golden grain grows easily makes for a classic image of heiros gamos (‘divine marriage’), a sexual union of deities that benefits humankind—and helps a family survive another long winter. (cf. a memorable description from folklorist Hilda Ellis Davidson (1969: 72); the interpretation of Sif as earth and grain has a long history, cf. Grimm 1882: 309-310)

Additionally, Grímnismál contains a curious reference to Thor wading every day through Kǫrmt and Ǫrmt, boiling rivers, and the two Kerlaugar (also rivers and, judging by the name—‘kettle baths’—also hot) to meet at the gods’ assembly. This seems to be a problem specifically for Thor, as the rest of the gods appear to ride horses. (Neckel & Kuhn 1983: 63) It’s tempting to associate Thor’s trouble with land-based bodies of water with his foretold battle with the sea serpent Jǫrmungandr, who dwells deep in the sea—as referenced throughout the corpus, the chthonic water entity must one day battle the heavenly water entity, Thor.

Another deity seems to have a very different relation to the Nine Wave Women. In the corpus, we’re told that the enigmatic god Heimdallr—there’s really no better way to describe this deity than that—is born from Nine Mothers, all sisters (from the lost Heimdalargaldr, Faulkes 1995: 25-26). This is a puzzling, even riddling, expression: How exactly can one be born from nine mothers? But this puzzle is easily resolved if we, as various scholars before us, consider the sister-mothers of Heimdallr to be the same as the Nine Daughters of Rán and Ægir, and understand the deity to be born from the waves, an origin similar to the Ancient Greek goddess Aphrodite (motif A114.1. “Deity born from sea-foam” but compare also A1261.1. “Man created from sea-foam” and T547.1. “Birth from sea-foam”) —certainly a fitting birth for such an anomalous entity.

Other deities are also strongly associated with water bodies in the North Germanic record. The most obvious example is the god Njǫrðr, memorably described in Gylfaginning as follows:

He lives in heaven in a place called Noatun [‘ship-places’]. He rules over the motion of the wind and moderates sea and fire. It is to him one must pray for voyages and fishing. He is so rich and wealthy he can grant wealth of lands or possessions to those who pray to him for this. (Faulkes 1995: 23)

Gylfaginning follows this description with discussion featuring two otherwise unknown stanzas, references to a more widely known narrative. This narrative likely took the form of a missing eddic poem (for relatively recent discussion on the narrative's apparent echoes in Skáldskaparmál and its ‘rationalization’ in Saxo’s Gesta Danorum, see Hopkins 2012) that strongly emphasizes a dichotomy of water and land. As scholar Bruce Lincoln concisely observes:

As is obvious, this text establishes a set of binary oppositions that contrast not just Njorð and Skaði, but also sea and land, harbours and mountains, ships and means of conveyance of snow, birds of the sea and predators of the forest, fishing and hunting, singing and howling … After nine days by the shore and nine in the mountains, all the oppositions are put back in place, Njorð and Skaði having decided that they are incompatible as ships and skis, summer and winter, seagulls and wolves. (Lincoln 1995: 25)

In this case, these stanzas also present the god as dwelling in the sea, which he clearly represents, and so he is perhaps to be understood as personifying the sea in the animistic manner we see in the case of Ægir, Rán, and their children. Njǫrðr's family also maintains a strong association with water. Going back to the Proto-Germanic period, the linguistic precursor to Njǫrðr (Proto-Germanic *Nerþuz, Latinized as Nerthus in Roman senator Tacitus’s 1 CE Germania) has a particular aquatic association. Unlike Njǫrðr, *Nerþuz is female, but a ‘female Njǫrðr’ is also present in Old Norse sources: Njǫrðr’s Sister-Wife (for whom the record mysteriously furnishes no clear name—she is mentioned both in Lokasenna and Ynglingasaga and may be represented in the theonym Njǫrun, see discussion in Hopkins 2012). We are told by Tacitus that a depiction of Nerthus is kept in a sacred grove and carried around the countryside before being ritually ‘washed clean’ in a lake and her attendants drowned there. This ritual placement in water appears to reflect the deity's association with water at a much earlier date.

Njǫrðr’s association with the sea is also emphasized in an eddic stanza in which the deity Loki ritually insults various deities. In this stanza, Loki tells Njǫrðr that “the daughters of Hymir used you as a pisspot and pissed in your mouth” (Larrington 2014: 86). So, who are these daughters, and why would they be “using” this deity so strongly associated with the “sea” as a “pisspot”? While no narrative containing this odd image—at least explicitly—comes down to us today, Thor’s encounter with a jǫtunn woman who makes a river swell features strong parallels in Skáldskaparmál:

Then Thor saw up in a certain cleft that Geirrod’s daughter Gialp was standing astride the river and she was causing it to rise. Then Thor took up out of the river a great stone and threw it at her and said: “At its outlet must a river be stemmed.” He did not miss what he was aiming at, and at that moment he found himself close to the bank and managed to grasp a sort of rowan-bush and thus climbed out of the river. (Faulkes 1987: 82, formatted for display)

Here Gjálp seems to be urinating into the river, causing it to swell. This incident is referenced in several other Old Norse sources and, we’re told in preceding Skáldskaparmál prose, and this river is called Vimur, “best of all rivers”. The daughter’s name, Gjálp (likely from gjálpa ‘roar’ but compare gjálfr ‘din of the sea, the swelling waves’, Cleasby & Vigfusson 1874: 202), happens to also be one of the names of Heimdallr’s Nine Mothers—discussed above—as recounted in Vǫluspá hin skamma (Neckel & Kuhn 1983: 294). Are we to understand this narrative as an animistic means of describing Thor’s problem with a ferocious, personified river, in line with Thor’s encounters with the brutal Wave Women of Læsø? And are we to understand Loki’s comment as a reference to rivers (the daughters of Hymir) draining into the sea (Njǫrðr)? Given what we’ve reviewed, Carolyne Larrington’s observation that “the daughters … are conceivably the rivers which flow down to the sea” (Larrington 2014: 295) seems quite reasonable.

Njǫrðr and his unnamed Sister-Wife produce two children: The deities Freyr (‘Lord’) and Freyja (‘Lady’). The two have much in common with their parents, and together these four are known as the Vanir, a particular group of gods. Freyr possesses ‘the best of ships’, Skíðblaðnir, and Freyja bears the name Mardǫll. Mardǫll is a dithematic name, meaning it is composed of two elements: the first element is broadly agreed to mean [‘sea’] (Old Norse mar- is cognate with the first element of modern English mer-maid) while the second element is less clear but may mean [‘light’], producing a meaning somewhere along the lines of [‘sea’] + [‘bright’]. Freyja, too, may have been associated with the sea in other ways, as we’re told that her afterlife hall Sessrúmnir ('roomy-seats') is located in a meadow, Fólkvangr, and Sessrúmnir also occurs in a list of ship names, invoking the image of stone ships settings found in fields in Scandinavia. In 1 CE, Tacitus tells us the ship is a symbol associated with a Proto-Germanic goddess he interprets as “Isis”. (On these topics, which may indicate a Proto-Germanic meadow—*wangaz—of the dead with watery associations, see discussion in Hopkins & Haukur 2011). We’ll discuss stone ship settings further in a section below.

The Old Norse record tells us of other goddesses dwelling in or around water bodies. One of them is the well-attested goddess Frigg, who dwells in a location called Fensalir (‘fen halls’—a fen is a type of swamp or wetland), and the goddess Sága lives in Sǫkkvabekkr (‘sunken bank’?), where she drinks with Odin. Freyja’s aquatic associations are also in line with this theme. The continued association between goddesses and water bodies raises interesting questions, particularly in light of the so-called ‘pole gods’—generally considered to be depictions of deities— found placed in bogs in Denmark and elsewhere. (Mimisbrunnr.info is currently developing a piece on this topic but until then we recommend this excellent English Wikipedia article on the topic.)

Old Norse sources repeatedly refer to water as the blood of a cosmic entity, Ymir. This primordial figure is killed by three deities (there’s that number again), who dismember Ymir and from his corpse form the cosmos, which includes the land, sea, and sky. From his blood comes the seas, and so Ægir and Rán, then, are presumably to be understood as descending from the blood of the primordial being. As a motif, the notion of the dismembered cosmic proto-entity—here represented as Ymir—is truly primordial: Scholars have long noted the extraordinary similarities between references in the Old Norse record and among related peoples (specifically Indo-European peoples) but also among peoples distant in time and place, such as in China, and some scholars have gone as far as promoting a Stone Age origin for this motif complex. (For a fairly recent survey of this classic observation, see Witzel 2017).

Another being from the earliest layers of ancient Germanic folklore is what we today know as the nix (*nikwaz ~ *nikwuz, Orel 2003: 287), although the characteristics of this being are unclear beyond its close association with water. English and German readers may be most familiar with this entity from a literary wonder tale (Märchen) authored by the Brothers Grimm known as Die Wassernix or The Water-Nixie. (This particular narrative occurs as item number 79 in volume I of the first edition of Kinder- und Hausemärchen 1812 and was adapted by the Grimms from material provided by informant Marie Hassenpflug, d. 1856). For readers unfamiliar with this material, we recommend folklorist Jack Zipes’s 2014 English translation of the first edition of Kinder- und Hausemärschen, which Zipes has titled The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (published by Princeton University Press.)

Scandinavian readers are likely to have encountered a famous depiction of the North Germanic extension of this entity in Theodor Kittelsen's Nøkken (1904), where it is memorably depicted as an eerie, glowing-eyed presence in an otherwise still pool. A certain malice associated with the creature has a long history: As early as Beowulf, the Old English extension of the Nix, the nicor appears as an aquatic entity that troubles the poem’s protagonist. In fact, Beowulf is awash with references to water entities, including the sea personified as the “spear-man” (gār-secg, lines 49, 515, & 537; perhaps an archaic reference to an Old English concept of Ægir or Njǫrðr). Beowulf encounters a few foes during the poem, including Grendel and his unnamed mother, who lives under water and is described as a goddess-like entity: The poet refers to Grendel’s mother as an ides (in the phrase ides aglæcwif, line 1259) and this word is generally considered cognate—extending from a common linguistic ancestor—with a common noun in Old Norse, dís, a word that refers to a goddess or a group of goddess-like women, the dísir. The dísir are entities closely connected to overlapping varieties of groups of goddess-like women, namely the valkyries and norns. (Compare, for example, the name Vanadís—meaning ‘dís of the Vanir’—for Freyja and Ǫndurdís—meaning ‘snow-shoe dís’—Skaði. This yields an image much like the goddesses who dwell in watery locations in the Old Norse record.

While the nixie is certainly ancient, it is not the most famous aquatic entity known from the ancient Germanic record: That honor goes to the mermaid. For example, one of the most famous statues in the world depicts a mermaid, and it is this image that represents the largest city in Scandinavia, Copenhagen, more than any other. This iconic bronze statue is the work of Danish-Icelandic sculptor Edvard Eriksen, who unveiled it in 1913. Eriksen named it The Little Mermaid (Danish Den lille Havfrue) because it was inspired by a literary fairy tale of the same name by Danish Hans Christian Andersen (d. 1875). In constructing his literary fairy tales, Anderson drew from a combination of native Danish folklore but also the literary works of his precursors, such as Germanic romantic author Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s famous novella Undine (1811).

Folklore featuring ‘sea spirits’—which we should go ahead and define as simply people who live in the sea, and, to be clear, not necessarily fish-tailed—is well-recorded all along the lengthy coasts and tributaries of Scandinavia. Much as in the case of the failed union of Njǫrðr and Skaði (it would seem no heiros gamos here, alas), the motif of the inconsolable separation of land and sea appears as a strong thematic element throughout these tales, where humankind represents land and the merfolk represent water. (For excellent discussion on this, see Dumézil 1973: 213-229)

The existence of specific bodies of water may also be explained as the byproduct of activities by a supernatural entity. For example, in Gylfaginning, the goddess Gefjun is said to have formed the Danish island of Zealand from Mälaren, a lake in Sweden, by way of plowing it with her oxen sons (an impressive statue dramatically depicting this event, the Gefion Fountain by Anders Bundgaard, d. 1937, stands in Copenhagen, by far the largest city on Zealand). Such animal-driven foundation tales have a long history: For example, in more (comparatively) modern Danish folklore, the Limfjord in northern Jutland is sometimes attributed to the activities of a great boar, the Limgrim, who is said to have dug it up.

The body of myths we today call Norse mythology contains no shortage of rivers, seas, or other bodies of water, including springs and wells. What is already a lengthy Kvasir Symbol Database entry would be need to be greatly expanded to cover all of these references, but given that the importance of the term Mímisbrunnr to the project, the entry would be remiss without discussing these topics. Old Norse sources state that three major roots stem from Yggdrasil, and that these roots draw from three springs. One of those springs is Urðarbrunnr (‘Well of Urdr, Well of Wyrd’) where three goddess-like women, Norns, bathe the great sacred tree Yggdrasil, the center of existence:

I know an ash stands,

it’s called Yggdrasill;

a glorious and immense tree,

wet with white and shining mud;

from there dew falls to the dales,

forever standing green over Wyrd’s Well (Urðarbrunnr).

(Hopkins 2020, normalized Old Norse in Neckel & Kuhn 1983: 5)

Another of these springs is Hvergelmir, which we are told in the eddic poem Grímnismál is fed from water dripping from the antlers of the stag Eikþyrnir that causes ‘all waters to rise’ (Neckel & Kuhn 1983: 62), but the third is Mimisbrunnr, the namesake of the present website. In this pool the god Odin gave his eye for knowledge, the god Heimdallr placed his ear, and from it the primordial entity Mímir drinks daily (and after whom it is named: ‘Mimi[r]’s Well’). Just as living trees and the ancient sacred trees and groves of the ancient Germanic peoples, even the center of the existence—the greatest sacred tree of them all—must drink from a water source.

There's plenty more to say about this topic but the the physical landscape—or waterscape, rather—of the ancient Germanic peoples clearly teemed with notions of entities personifying or dwelling within the water (or perhaps both): the water both contains life and is itself alive.

Engaging with water: Ship symbolism & voice deposits

The concept of the ship, a vessel used by humankind to maneuver over water, plays a major role in death customs among segments of the North Germanic and West Germanic peoples. Not only have numerous ships been discovered within burial mounds, such as the famous Anglo-Saxon burial sites in England (such as Sutton Hoo and in Snape) and the Viking Age Gokstad and Oseberg ship burials in Norway. In addition to these, archaeologists have discovered a tremendous amount of smaller burials and larger burials. Some of these stone settings contain graves.

Stone settings across Scandinavia are also commonly identified by scholars as representing ships. The highest concentration of these ship settings exists just outside of Aalborg, a city in northern Jutland, standing in a location known as Lindholm Høje. In southern Jutland, an enormous example—the largest known ship setting— exists under the Jelling Stones, one of which declares Denmark to have been Christianized.

When not buried or represented iconographically, ships could also be burned in a dramatic fashion. This process is not only mentioned in myth, where we learn of the beloved god Baldr's funeral in Gylfaginning, but also in practice, as in Risala, where 10th century Arabic traveler Ahmad ibn Fadlan records witnessing such a funeral among the Rus’, a community of North Germanic traders whose name would go on to become modern day Russia. (Readers can compare all English translations of Ibn Fadlan’s Risala here)

From around Tacitus’s time to hundreds of years after (from around the first to fifth centuries CE), archaeologists have unearthed numerous depictions of ancient Germanic goddesses in areas where the ancient Germanic peoples intersected with the far reaches of the Roman world. Most of these female deities appear in in trios, the Matres and Matronae, but there are also depictions of singular deities. One such singular deity is Nehalennia, a goddess who is often depicted with her foot on a ship, and her altars appear to have been placed in connection with nautical routes on the North Sea coast of what is today the Netherlands. (Nehalennia is often depicted with a container of what appear to be apples, and the apple tree and its fruit are symbols that readers can find more information about here.)

The oldest known depictions of ships in the region occur with great frequency in Bronze Age Scandinavian art. These appear on stone but also on objects, such as metal razors. A large amount of these razors are in the National Museum of Denmark’s collection, a topic largely exterior to the scope of the present Kvasir Symbol Database entry.

The self-sacrifices of Odin and Heimdallr echo votive deposits (a placement of an object without intention of recovery for religious purposes) made by the ancient Germanic peoples in bogs and other water bodies in Northern Europe. Whether as part of funerary culture among the ancient Germanic peoples in the region or as some variety of sacrifice, numerous human corpses intentionally placed in bogs — known today as bog bodies — have been discovered in bogs in the region. These human remains are uniquely preserved due to the chemical composition of these wetlands, and the unique makeup of the bog has also preserved various other items, including what are generally identified as depictions of deities, the so-called ‘pole-gods’. One can witness a related custom today in the placement of coins in water bodies such as fountains throughout the West.

Image II: The god Njǫrðr personifying the might of the waves, reflecting the perceived etymological meaning of his name—‘power, strength, potency’. Rim Baudey for Mimisbrunnr.info, 2021

Analysis

The modern day linguistic descendants of the ancient Germanic peoples no longer personify bodies of water in a manner comparable to the examples found in North Germanic material. That said, similar concepts do make their way into modern popular culture in the West, particularly by way of the medium of animation. Animation, where for example a hammer can grow a face and chase a taunting nail, appears to be a particularly conducive means of presenting animistic concepts.

Examples comparable to the material above notably occur in Studio Ghibli’s Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001), where personified rivers play a key role throughout the film, and Ponyo (Hayao Miyazaki, 2008), which follows the life of a goldfish initially named Brunhilde. The latter film is highly influenced by the Old Norse Vǫlsunga saga (readers can find R. G. Finch’s excellent translation online here) by way of German artist Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen extraordinarily influential opera cycle (premiered 1876) along with Andersen’s above mentioned The Little Mermaid. Ponyo in particular shows the sustained value of the motif of the separation of land and sea, as the collision of the two leads to tremendous imbalance in the tale’s narrative until Ponyo fully commits to life on land.

Guillermo del Toro’s film The Shape of Water (2017) invokes similar motifs, again highlighting the conflict that arises with the meeting of water and land and the disasters that can ensue, only resolved by the two once again parting, in this case with the protagonist joining a merman. Mermaids feature commonly in Western folk culture, particularly in shoreline communities, where mer-folk (and in particular mermaid) imagery is difficult to miss. Copenhagen’s famous statue is ultimately just one example among many thousands and, in some rare instances, instances of this extremely popular motif can be found quite far from any notable water bodies, such as the Sip n’ Dip mermaid bar in Great Falls, Montana.

Nonetheless, industrialization drives modern views of water in the West: In all its forms, water—the source of all life on the planet —is today generally considered to be nothing more than a commodity to buy or sell, a necessary substance for industrial production and human habitation. Any trace of personification of the sea is generally limited to media works such as those discussed above.

The situation is rather different elsewhere. As early as Vedic India, the river Ganga (commonly known in the west as the Ganges) is personified as a goddess of the same name. Similarly, the goddess Saraswati once also personified a river. Exactly where this river was during the Vedic period remains something of a mystery, but Ganga personified continues this focus on female deities dwelling in watery places as discussed in the ancient Germanic record above. (For a famous Vedic hymn celebrating personified rivers as goddesses, including Ganga and Saraswati, among the Rigveda texts, see “X.75 (901) Rivers” in Jamison & Brereton 2017: 1504-1505.)

Modern Hindu veneration of the river Ganga offers a little insight of what veneration of a personified body of water might look like in the ancient past, including among the ancient Germanic peoples, but it also highlights the fact that the world’s waters are experiencing considerable human-caused change. While Ganga is certainly one of the most beloved and venerated water bodies in the world, it is also severely polluted, and the dominantly Hindu state allows for this by tolerating, for example, leather tanneries on its banks—which leach toxic chemicals and heavy metals into the river—and continuing to allow for the disposal of raw sewage directly into its waters, where adherents bathe, worship, and conduct funerary rituals. Ganga is hardly alone. The world’s oceans are experiencing intense and ever-increasing levels of pollution, acidification, and warming due to human activity. The days in which humankind’s influence on water systems was limited and relatively nondestructive are long gone.

Germanic Heathenry, a contemporary religious movement that draws from modern reception of elements of the ancient Germanic record, has historically placed very little emphasis on topics like animism (and a variety of other fundamental aspects of ancient Germanic paganism, such as the historic central importance of sacred tree and grove veneration).

A movement among a group of academics toward a modern expression of animism, a so-called new animism, has developed in recent years with a strong emphasis on modern scientific understandings of ecology. The most notable visible figure in this school to date is British scholar Graham Harvey (The Open University). More localized to ancient Germanic studies, individuals such as Danish academic Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen (Uppsala University, read a 2019 interview with Rasmussen at Mimisbrunnr.info here) have embraced a notion of historic Germanic heathenry-associated animism. Rune and his colleagues’s approach has received some media attention in Denmark, particularly by way of articles in the major Danish newspaper Politiken, and beyond by way of Rasmussen’s YouTube channel and Nordic Animist Calendar.

About the images

This entry contains three original pieces by Rim Baudey for Mimisbrunnr.info, all produced by the artist in 2020. They are as follows:

I: The Nine Daughters of Rán and Ægir, the personified waves. Here the sisters churn the seas.

II: The god Njǫrðr personifying the might of the sea, reflecting the perceived etymological meaning of his name: ‘power, strength, potency’.

Readers can find wallpaper-quality versions by clicking the images. Please contact Mimisbrunnr.info for image use requests.

Further reading

For a more in-depth look at Rán as particular, see scholar Judy Quinn’s excellent article on references to the deity in the Old Norse corpus:

Quinn, Judy. 2014. “Mythologizing the sea: the Nordic sea-deity Rán” in Tim Tangherlini, ed., Nordic Mythologies: Interpretations, Institutions, Intersections, The Wildcat Canyon Advanced Seminars: Mythology 1, p. 71–97. North Pinehurst Press. Viewable online.

References

Cleasby, Richard & Gudbrand Vigfusson. 1874. An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Oxford at Clarendon Press.

Davidson, H. R. Ellis. 1969. Scandinavian Mythology. Paul Hamlyn.

Dumézil, Georges. 1973. From Myth to Fiction: The Saga of Hadingus. The University of Chicago Press.

Faulkes, Anthony. 1995. Edda. Everyman.

Faulkes, Anthony. 1998. Edda: Skáldskaparmál 1. Viking Society for Northern Research. Online.

Fulk, R.D, Robert E. Bjork, & John D. Niles. 2008. Klaeber’s Beowulf. 4th edition. University of Toronto Press.

Grimm, Jacob. 1882. Teutonic Mythology, vol. 1. James Stallybrass trans. George Bell & Sons.

Harvey, Graham. 2017. Animism: Respecting the Living World. Second edition. Hurst.

Hopkins, Joseph S. 2012. “Goddesses Unknown I: Njǫrun and the Sister-Wife of Njǫrðr” in RMN Newsletter 5, p. 39-44. University of Helsinki. Online.

Hopkins, Joseph S. & Haukur Þorgeirsson. 2011. “The Ship in the Field” in RMN Newsletter 3, p. 14-18. University of Helsinki. Online.

Jamison, Stephanie W. & Joel P. Brereton. 2017. The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Vol. III. Oxford University Press.

Larrington, Carolyne. 2014. The Poetic Edda. Oxford University Press.

Lincoln, Bruce. 1995. "The Ship as Symbol: Mobility and Mercantile Capitalism in Gautrek's Saga" in Birgitte Munch Thye & Ole Crumlin-Pedersen (editors). The ship as symbol in prehistoric and medieval Scandinavia: papers from an international research seminar at the Danish National Museum, Copenhagen, p. 25-33. Nationalmuseet.

Neckel, Gustav & Hans Kuhn. 1983. Edda. Die Lieder des Codex Regius nebst verwandten Denkmälern. Universitätsverlag Winter.

OED. 2020. “animism, n.2.” OED Online. Oxford University Press. Online: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/7793?redirectedFrom=animism (accessed February 25, 2021).

Orel, Vladimir. 2003. A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Brill.

Thompson, Stith. 1955. Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, vol. 6.2. Indiana University.

Witzel, Michael. 2017. “Ymir in India, China - and Beyond” in Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, Jens Peter Schjødt, & Amber J. Rose. Editors. Old Norse Mythology in Comparative Perspective. Harvard University Press.